Eighty years ago, Hitler's friends wobble whilst Britain (accidentally) flags its firmness

Hitler’s decision to invade Poland that he had

revealed to his military commanders at the Berghof remained concealed, so the

rest of Europe could only observe the outward signs of the final crisis: the

last, open German demands on Poland, sundry German delaying tactics to keep

its opponents guessing, the frantic attempts by other powers – above all Britain

- to avoid a conflict and the more-or-less ambiguous moves by countries more

usually friendly to Germany to reserve their positions. For outsiders there

were still grounds for hope, but not optimism.

There was a crumb of comfort for the peace camp

from the announcement by General Franco that Spain would remain neutral in any

conflict. The German-Soviet pact was given as a pretext, but the ravages of the

Civil War which had ended only a few months before, left Spain in no position

to pose any threat to France or even to defend itself.

Italy’s attitude was harder to decode, but here too

optimists had something to work on. The tone of rhetoric was pro-German but

Mussolini made no public pronouncement of a firm intention to support Germany

in any conflict. In private Mussolini had declined to be dragged into a war

provoked solely by German aggression. He knew that Italy’s economy was too weak

and potential gains were small. The much-vaunted Pact of Steel between the two

Fascist dictators was made of considerably weaker material.

Almost unnoticed by anyone, Britain and Poland had

been discussing the wording of a formal treaty to embody the unilateral

guarantee that Britain – backed by France - had issued some months before. By

chance the treaty was signed publicly the day before Germany planned to invade.

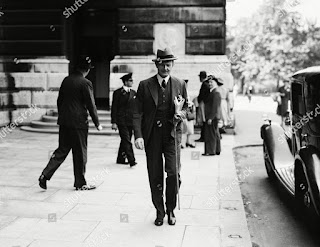

It was signed by Lord Halifax, the British Foreign Secretary, and Count

Raczynski, the Polish ambassador to London, and the signature itself at the

Foreign Office had none of the flourish and drama of the Ribbentrop-Molotov

pact. No photographers were present and the Count did not pose for this photo outside

the Foreign Office, but the treaty still came as something of a surprise to the

Germans and may have affected their moves.

At the shortest possible notice, German plans to

invade Poland were put on hold. Mussolini’s craven back-tracking was the main

cause, but the Anglo-Polish treaty played a part as well.

A mysterious German intermediary arrived in London

about whose mission and doings nothing was disclosed; only his visit was known

about publicly. Again, the optimists had something to work on. The man was

Birger Dahlerus, a Swedish industrialist, with close ties to Hermann Goering.

His name was garbled into a semi-official code-name in the British Foreign

Office: “the Walrus.” In reality his mission was futile; Britain would offer

him nothing that they would not offer formally to Germany and he spoke only for

Goering. The only purpose of his journey lay in the competition amongst the

Nazi leaders, not in any meaningful diplomacy. If the British buckled at the

last minute, Dahlerus’s involvement would give Goering a pretext to claim the

credit from Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop.

The IRA claimed its first fatal civilian victims in

its “S Plan” bombing campaign in mainland Britain. Five people were killed and

a further 70 injured in an explosion in the Broadgate shopping street in

Coventry. The precise target of the bomb is the subject of the customary fog of

contradictory claims, including one that the detonation was an accident. It was

the worst terrorist attack in mainland Britain until the 1970s. The

perpetrators were rapidly arrested.

Comments

Post a Comment