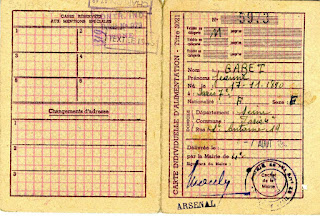

Eighty years ago, the French are told (almost literally) to tighten their belts whilst the British government uses augmented wartime powers for rather less honourable purposes

The French finance

minister, Paul Reynaud, gave a radio broadcast setting out a series of economic

measures to the public. Chief amongst these was the planned introduction of

food rationing. This came some months after Britain had brought in similar

measures. With five million men mobilised for war, France’s still heavily

agrarian economy was in a poor position to meet the population’s food needs. Prices

had started to rise. The war was clearly going to last well beyond the next

harvest so the move was pre-emptive. On the demand side of the equation, the

government would subsidise the import of foreign labour and the cost of spring

sowing; the price of fertilisers would be brought down.

In ceremonies redolent of

the wars of early in the previous century, the ships’ crews of Ajax and Exeter

which had defeated the Graf Spee in the Battle of River Plate were fêted

on their return to London. They were inspected by the King, paraded through the

capital and treated to a grand formal luncheon at the Guildhall as guests of

the Lord Mayor of the City of London. The old-fashioned flavour to the

proceedings was deepened by the praise lavished on "the

brave sea captains and hardy tars who won the battle of the River Plate"

by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. The utmost propaganda

value was being wrung out of Britain’s one notable achievement so far in the

war.

All of

Scotland north of the Great Glen, including the isles, was declared a “protected”

military area by the War Office. Under the Defence Regulations, this lay in its

power, a clear indication of how much civil liberties had already been

suspended. A War Office permit would be required to enter the zone. Downing Street speedily made use of another aspect of the government’s enhanced powers which

had been less openly stated and this for purposes unrelated to the war. The

phone of the leader of the opposition Liberals, Sir Archibald Sinclair, was

tapped without the need for a Home Office warrant. Because he lived in the

area covered by the defence regulations a warrant was not required. Almost needless

to say, the content of his phone calls was used for purely political purposes. Chamberlain

made a point of informing Sinclair that he was under observation.

Comments

Post a Comment