Eighty years ago, jealousy between the dictators helps spread the war into the Mediterranean

In one of the war’s most pointless follies Italy launched an invasion of Greece. It is hard to find any material justification for the move, on strategical or economic grounds. It is just conceivable that Mussolini imagined that Greece would cede the territory that he was demanding – on no legal or historical basis whatever – and grant him a bloodless victory. Otherwise it was aggression for the sake of aggression. The invasion of Albania in 1939 could - just – be viewed as a step to cement control of the Adriatic and exert pressure on Yugoslavia but Greece was no more than a senseless southern expansion of the Italian “empire.” The decision was in part due to Mussolini’s sense of inferiority towards Hitler, whom he felt subordinated Italy to German expansionary moves without consultation. Here he could play the same trick on Hitler. Futile as it was, the invasion of Greece expanded the geographical scope of the war into both the Balkans, which had been uneasily peaceful, and the Mediterranean where Britain had retained its strategic upper hand despite the fall of France.

At least in the eyes of later historians and bureaucrats the Battle of Britain ended on 31st October. In practice it had been decided in late September when Germany postponed indefinitely the invasion of Britain. The only practical effect of the date was in setting the eligibility for aircrew to receive one of the rarest decorations of the war, the Battle of Britain clasp to the 1939-1945 star which was instituted at the end of the war. Fewer than 3,000 men were entitled, of whom about one fifth were not British. By the time the clasp was instituted a large number of those entitled had lost their lives. The date was also irrelevant to the war in the air. The Luftwaffe air raids on London and, soon, other British cities continued unabated and were to do until the following spring with heavy civilian casualties and ineffectual attempts by RAF night fighters to stop them which were probably more dangerous for the defenders than their intended victims.

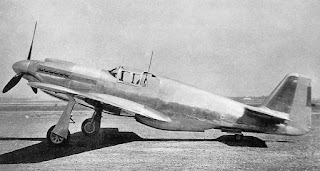

The prototype NA-73X fighter aircraft made its first flight in the US. It had been built to meet an order from Britain’s Ministry of Aircraft Production which had been granted a mere 102 days before, a precursor of the awesome power that was soon to develop in the US aircraft industry. Britain's own aircraft industry was hugely commited to making bombers and there was little scope to expand domestic production of fighters. The most noticeable technical feature were laminar flow wings which had low drag at high speeds. The plane that flew was powered by an Allison engine, which proved to be the design’s Achilles heel, with poor performance at high altitude, fatally compromising its supposed mission as an interceptor. It was only once it was fitted with a version of the Rolls Royce Merlin engine built by Packard in the US that the NA-73X blossomed into the P-51 Mustang, one of the war’s most successful designs and one of he most iconic aircraft of all time.

Comments

Post a Comment