Eighty years ago this week the best-prepared but highest risk military operation ever is launched.

The Germans withdrew towards northern Italy after the Gustav Line had been breached and the breakout from the Anzio beachhead. Marshal Kesselring declared Rome an open city as their forces withdrew; orders to destroy its bridges were ignored. Led by US general Mark Clark the Allies entered the city, the first European capital to be liberated.

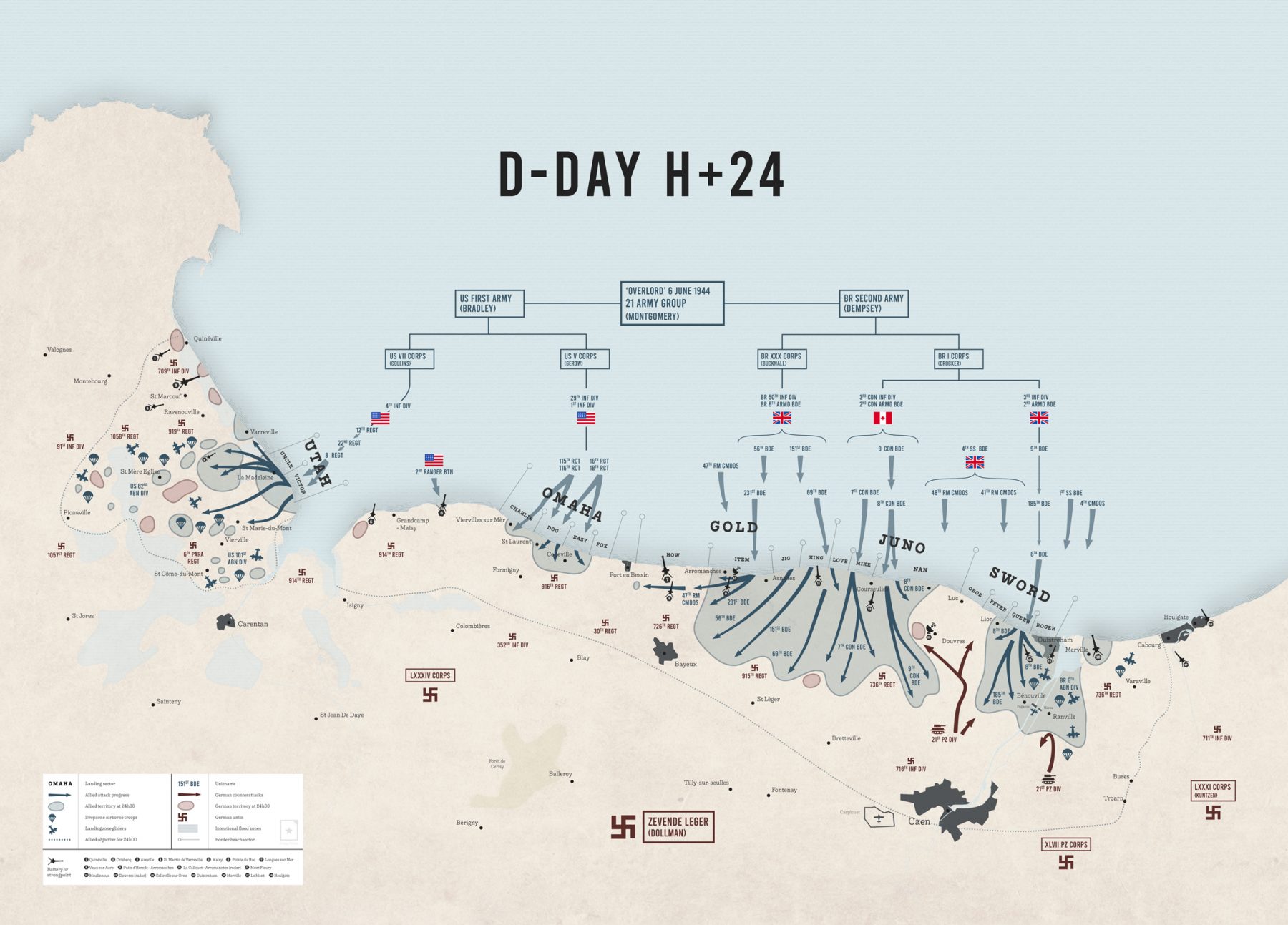

The news about Rome was immediately swamped by the D-Day landings in Normandy, probably the largest and best planned single operation of war ever undertaken. It was also arguably the highest risk operation ever. Only a few months before Churchill had been hoping to avoid the risk by attacking the Germans across the Adriatic into the Balkans. The allies were braced for the possibility of defeat; General Eisenhower, the supreme commander, had even written a communique announcing the failure of the attack. There was no significant fall-back or alternative plan. Field-Marshal Rommel had advocated a strategy of an all-out immediate attack on the beach-heads, which was rejected. Significant German forces were kept in reserve, in part against the imaginary danger - fostered by intensive deception measures - that the Allies would also land elsewhere.

The American strategic air offensive against the Japanese - Operation Matterhorn - began with a raid by the new B-29 bombers controlled by the dedicated XX Bomber Command from bases in India on targets in Bangkok. With a range of 2,000 miles the B-29 was one of the most advanced aircraft built. XX Bomber Command would soon move to bases in China from where it could bomb Japan itself.

The government announced that there would be special debate in Parliament on the measures proposed in the White Paper on employment concerning regional measures. The prime consideration was to prevent a recurrence of what happened in the 1930s when "special areas" became a short-hand for locations with massive unemployment due to structural and economic factors; the new term was "development areas". The driving force here was Labour's Hugh Dalton, the President of the Board of Trade. One specific goal was to establish light industry in zones where the heavy industries of coal, ship-building and metals had been ravaged by the great slump. It was assumed that far greater government intervention would be involved than had been accepted in the 1930s.

Comments

Post a Comment