Appeasement lags in Europe and tension builds in the Far East

Somebody must have reminded Neville Chamberlain that he had become

the Prime Minister in a supposedly national government rather than a Conservative

government supported by a couple of minor, fringe elements. A mass meeting of

the supporters of the three parties concerned was held at the Albert Hall,

which attracted a respectable audience of 8,000. The only precedent had been in

the election year of 1935. The giveaway were the representatives chosen to

represent the two minor parties: Malcolm Macdonald, son of the National

Government’s begetter, and one of the tiny handful of National Labour MPs, and

Sir John Simon for the National Liberals, a party affiliation that only

dedicated historians will recall. Chamberlain’s 45 minute speech was felt to be

rather perfunctory and the reference to the fact that it was his late father’s

birthday, redundant. Beyond deploring the failure of his plan for the German

Foreign Minister to come to London – appeasement was still very much on the

agenda – there was little of consequence.

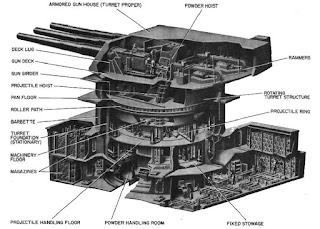

In the US it was clear that something should be done to deter

Japan. There was a financial/military left and right. The US Treasury announced

an agreement on a three way transaction involving gold and US dollar purchases by China matched

by silver purchases by the US with the goal of bolstering Chinese finances as

well as reflating the US economy. On a more practical level the State Department

confessed bafflement at the failure to obtain general agreement for naval arms

limitation and “reluctantly” announced that two new battleships would mount 16”

guns in place of the less powerful 14” originally anticipated in negotiations.

Comments

Post a Comment