Eighty years ago, blacked out British roads kill more people than the Luftwaffe

Stalin

continued in his attempts to remake European diplomacy in the wake of his

partition of Poland in partnership with Hitler. His largest move met with a

resounding failure. He might have abandoned his old Bolshevist heritage in many

ways, but he retained a near-paranoid suspicion of Britain as the most vigorous

military enemy of the Russian Revolution. He tried to browbeat Turkey into agreeing

to come to the Soviet Union’s assistance should Britain and France attack. The

Turks, though, understood that the Soviet Union posed a far greater threat than

the western powers and signed a mutual assistance pact with Britain and France.

This provided one of the bedrocks of Turkish neutrality through the war which

ultimately worked firmly to the benefit of both sides.

Stalin’s

demands to Finland met with an equally cold response. A Finnish delegation left

Moscow after a stay of barely hours after they had been presented with a

catalogue of territories that they were expected to surrender together with a

dismantlement of border fortifications. Faced with Soviet military power, many

in Finland would have been willing to accede, but in the end the futility of trying to appease Stalin was recognised.

One of the war’s

largest land battles since the end of the Polish campaign took place on the Maginot

Line. French casualties were publicly described as “ridiculously low.” They

were set against 5,000 casualties supposedly inflicted on the Germans. Both

claims lay firmly in the realms of propaganda. The German attack which inspired

them was no more than a local holding operation involving small forces. Britain and France were fighting a Phony War in more ways than one.

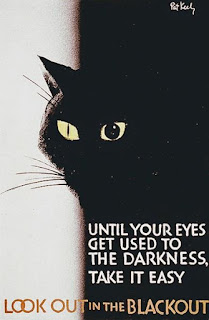

The war was

proving unexpectedly deadly for Britain’s civilian population. Statistics were

published showing that more than double the number of people were killed in

traffic accidents – some 1,100 - in September 1939 than in the preceding month

or in September 1938. Pedestrians accounted for practically all the incremental

fatalities. The direct cause was the rigorous imposition of the black-out

designed to hamper German air raids. Only once the Battle of Britain and the

attendant Blitz got under way almost a year later did the Luftwaffe

begin to kill more than a tiny fraction of the number of British civilians who

died on the roads.

As part of

organising Britain’s economy to meet the requirements of total war, Chamberlain’s

government came to accept the need for a ministry of shipping as had existed

during the First World War. Britain’s pre-war contingency planning – which was fatally

compromised by Chamberlain’s delusion that war would never come thanks to his

efforts – had not featured one. Whatever kudos Chamberlain might have earned from

this rather belated acceptance of reality was undermined by his choice of

minister. Sir John Gilmour was an elderly Scottish grandee, who had stepped

down from full time politics some years before. He brought neither energy,

dynamism nor technical knowledge to the work and hardly strengthened the

political clout of the government. Quite why he was selected remains

mysterious. Chamberlain’s civil service advisor, Sir Horace Wilson, was blamed

for the choice by government critics for interference in the political process.

Wilson certainly exercised a powerful influence on the choice of ministers, but

he favoured technocrats untainted by political ambition.

Comments

Post a Comment