Eighty years ago: the Sun Drops Below the Hills of the Raj and Rises over the Alps of the Third Reich

Unconsciously King George VI

sounded the death-knell of the British Empire in India with the announcement that

he would not be travelling there for a Coronation Durbar the following

winter. The formal proclamation of the British monarch as Emperor or Empress of India

had been the cornerstone of Britain’s constitutional position in the

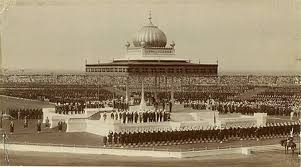

sub-continent. It was a prime example of a great tradition that only happened

once. There had been Durbars for Victoria and Edward VII but they had not been present in person. The only King/Emperor to attend his own Durbar was George V in 1911 at apogee of the Empire's might. The

ceremony was a byword for magnificent lavishness and was held in a huge,

specially built amphitheatre. Edward VIII had dragged his heals over any

thought of participating in a similar ceremony, as he did in all things

concerned with India. As Prince of Wales he had resisted his father’s wish for

him to visit India. His brother naturally took a more dutiful approach, but the

huge cost of such an event and – not that London admitted it was was consideration – Indian nationalism combined to

force postponement, for ever as it turned out. The political establishment had pulled out all the stops to ensure that his coronation as King of Britain succeeded so as to give a stamp of full legitimacy to his uncomfortable and unexpected succession but the tank had run dry. George was the last sovereign to

bear the proud Ind. Imp handle but

the global cataclysm that lay ahead meant that he would also lose it.

The London government’s scheme

for very limited political autonomy for India had never managed to get up and

running; it had not managed to fit enough wheels to ensure stability and

traction. Even those that had been fitted were now in process of coming off. Two

of the state government’s established under the new legislation in Bihar and

the United Provinces resigned because they could not over-ride the “reserved”

powers of the London-appointed (white) governors and order the release of

political prisoners.

Meanwhile in Central Europe Adolf

Hitler was operating an informal empire with a good deal more ruthlessness and

success. Kurt Schuschnigg, the Austrian Chancellor, had visited him at his

mountain retreat, the Berghof, to try to stabilize relations with Germany. He found

himself peremptorily instructed to reconstruct his cabinet to enhance Nazi

representation. In particular Arthur Seyß-Inquart, not yet a party member but

deeply sympathetic, was to be appointed as security minister with full control

of all police. Schuschnigg and Austria's President Miklas struggled to demur but they

were confronted by an insuperable force.

Comments

Post a Comment